Last week, my friend and I sat in the backyard of an outdoor market, sharing chemically-enhanced pink and yellow sodas, not understanding at first what the flavours were or how we were going to get our heads around the only non-alcoholic drink on the menu at the bar.

The day had been sweet, stuck in the mellowness of a bright and sunny afternoon. A lot of people bore a kind of backdrop smile on their face, wore flip-flops and flowy dresses that revealed translucent and veiny legs from skin exposed to the infamous lack of English sun. It didn’t matter. Fake-tan a bit of that, and no one would see the difference. At least that’s what we saw in the teenagers who hung around the Ministry of Sound entrance. We’d first walked in circles around Elephant and Castle’s roundabout, struggling to locate each other, calling on our phones through the sound of hundreds of cars passing by, traffic lights beeping for ten seconds and Cuban music played on an old stereo. It was after a while that we reunited in front of UAL.

When we sat down on the less-than-comfortable chairs in Mercato Metropolitano’s backyard, we didn’t know we were going to catch up through tears and deep family talks — but we did, like many other times before. All of it unfolded in sharp contrast to the table beside us: a never-ending birthday bash where new faces kept joining the larger-than-life group. Each newcomer brushed against our unstable garden table, its pink edge sharply digging into my shin. Each arrival was met with cheers, pints of amber IPA, and a tall, chestnut-haired guy with glasses who got up for hugs. I watched the wet rings they left in their wake, foreseeing empty piles by the end of the night.

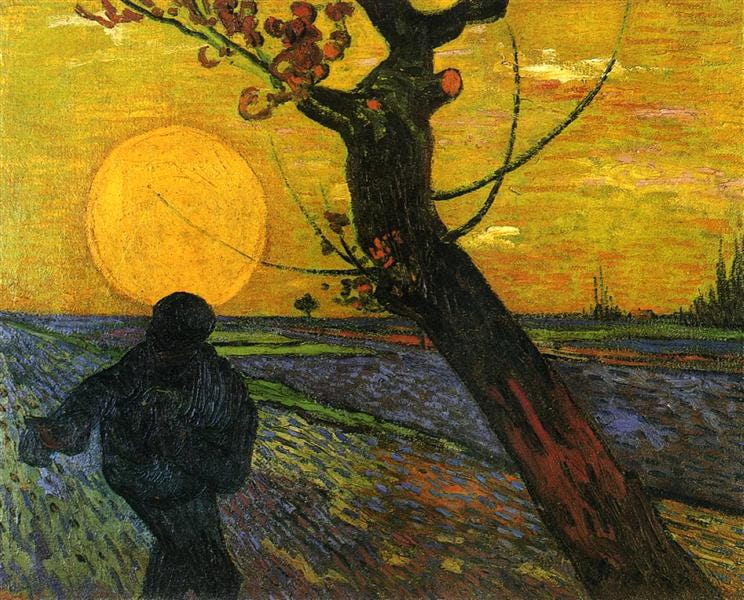

Our discussion, like many others in London that week, had centered around the sun, how it had blasted out of nowhere, lifting me out of post-winter misery. It was all I could talk about: like a plant, keen to grow, my face had pivoted toward the sun when it first showed up. I daydreamed on a balcony that had spent the colder months gathering dust and mold, and despite construction works drilling nearby, I relished in it. My skin was reminded of Italian breezes and Aperol Spritz, of the many summers spent lying on the grass in my grandparents’ garden, digging my face into the soil’s roots, not minding an ant or two crawling on my wrist. It all seemed far away now, but it was there just the same. It was then that my friend first mentioned the term enfant de la lune to me. I’d never heard of it before.

After I got home, as if the algorithm had heard me, my Instagram feed showed me a video about an enfant de la lune, translated as “moon child”. A woman in her twenties explains how she navigates the world wearing a space suit. Nothing like what Katy Perry and others might have worn during their recent expedition, all for promotion Musk’s new richest of the rich attraction. This was more like a life lived in filters, seeing the sun from afar, but never quite reaching its full potential, like an expedition that was never meant to be. Guys and St Thomas Hospital describes Xeroderma pigmentosum as “a rare, genetic condition that you inherit from your parents. A person with XP cannot effectively repair damage to the body caused by ultraviolet radiation (UVR) which is present in all daylight. XP is a lifelong condition. There is currently no known cure, but there are ways to manage it.”

Perhaps I’d always thought of myself as a moon child, never realising how I was anything but that. That evening, I sat down, and for once in many years, I looked at the sunset outside the window and surprised myself, begging for it again, and again, and watching out for the grey mud, the lifeless sky creeping back in, blading seagulls into nothingness, blurring the edges of the here and now, making me look for what's beneath. No clouds to even prickle your imagination. So where did it start? The fact that I’d spend half a life, hiding from the sun, refusing to even, at times, let it enter the room I inhabited.

The sun and I were off to a good start. I was the one who tanned in my family. When I look at pictures of us going on holidays in the Dordogne, where my uncle and aunt had settled, I see the tanned-skin girl — the one with tan lines marking where her shoulders meet her arms, her shins, her thighs. She smiles with nothing but liberty. She wears a top that reveals a figure too grown-up for a ten-year-old — or so she’s told. She wears Bermudas that go down to her knees. She hides the parts of herself she doesn’t want people to look at. Her mum still dresses her — or tries — in the kids’ section, but they both know that won’t last much longer. Only her sandals — chunky, beige, suede — give her a more childish look. She could be fifteen, sixteen, seventeen. But she’s a child. And she loves the sun. She runs under it, bikes alongside the river with her brother and cousin, and she can never get enough of it. It’s never too hot, nor too sweaty; it just bounces off her skin. And she walks the dog to wash it off — early in the mist, with her uncle — stepping into the morning dew, not caring if it trickles down her toes.

I grieve that girl. I lost her along the way.

Along the way came my obsession with being chronically online. I took away the sun from my life, drawing the curtains closed, hunching my back in front of a screen, but writing. Writing about, perhaps, scenes I’d forgotten. I remember the smudge of my eyeliner getting darker in the hotter months. My body sweating, cracking underneath the tights I insisted on wearing. For a long time, the sun became my enemy simply because, in adolescence, it was hard to wear foundation alongside the sweat. It made the acne flare up more, the bacteria live off it. But I insisted. I didn’t want anyone to see. So I retreated from the life where people could see, and what better way to do than to flee from the sun? My mum sometimes came in my bedroom, flinging the curtains open, asking why I was in the dark. I didn’t have a proper answer for her. Like a vampire, I flinched at the light.

As I went through my early twenties, I don’t remember it becoming much better, but I ignored the sun. It was part of life. It elongated smiles and shortened skirts, for the most part. For me, it became all about hiding my chubby thighs, my big body, my gigantic arms. I wished for winter to return, where I could slice more of me in layers, so no one would see what I hated looking at. There was something scary about putting my body on display. I envied the mini shorts, the dancer dresses, the liberty of getting your biceps in the air without frowning at your cellulite, the flab of your knees. I envied that, never capable of giving it to myself. It didn’t matter that I lost more than ten kilos at one point, it still wasn’t there. I didn’t want people to see the horror of me, and the sun, only highlighted it.

I remember that when I first started therapy, it wasn’t really me talking — it was my body hatred. I clung to the loathing raft I’d built for myself, and in the second session, I called myself a monster. I didn’t even notice, but the therapist repeated those words back to me, and I flinched. There was so much violence in my inability to hear it. But it was true. That was how I used to see myself: a monster, lurking on the uncomfortable kitchen chair in front of the Windows 2008.

I don’t know if I ever liked that version of me. Maybe this year, I’ve started to — just a little. If it wasn’t my acne or my body, there was always something, and I finally reconciled with the idea that maybe it was time to start living. There had always been summers where psoriasis dropped little coins of inflamed flesh on my legs, or where eczema invaded my upper back and thighs. In those moments, for a long time, I was back in the bedroom, feeding the monster. I heard it loud and clear, and it was hard to get out of it. And the sun didn’t just make me want to hide — it hurt. It stung as soon as it hit my raw skin. I tried to live life, but even taking showers made things worse. After that big episode, the eczema lingered on my hands. I tried to hide them behind my back, pulling my sleeves down as far as they could reach, stretching the fabric until it cracked at the seams. I watched the inflamed liquid seep from the crevices, glistening under the rays of sunshine. I recoiled at the thought of others seeing it. The warmth stabbed — spread fire across my limbs. I turned away. Applied sunscreen. Too much. Left ghostly undertones on my skin.

I tried so hard to live in this version of my skin. To accept it. Be positive. There were times when there was me, and then there was the skin, and I was looking from the inside out, trying to patch the two together. I spoke to my partner about what we were going to have for dinner. I tried to shop in the Tesco aisles, but somehow, I was never really there. My gaze always drew back to my hands, tears swelling behind my eyelids, disgusted by the sight. I tried to follow the conversations with coworkers at the pub. I gripped a glass of Diet Coke, served from a hose that was barely washed and lacked fizz. I sipped it as I smiled. We talked about my time in Vietnam. About how I never took risks in life. I resisted the urge to pull back, to retreat home. I stayed for an hour, an hour and a half. Then I put my sunglasses on and gave up — back to the comfort of not being seen, of not having anyone peer at the hands I wanted to cut off.

Ever since the summer returned this April, I’ve been thinking about all of this. I thought this summer would be another one spent lying in bed at the peak of August, legs spread, in underwear, stuck in a stuffy flat with all the curtains drawn — while neighbours roared and rolled on the grass in laughter, clutching gin tins, dropping liquid sideways as they talked, staining their blue jeans with grass, falling asleep on their lovers’ laps. I thought I’d scroll the internet endlessly for solutions, advice on what to do, what not to do, how to make my skin better. But no. It hasn’t happened. Not yet.

So this year, I’ve promised myself to drink spring and summer again. I let them melt against me. Dare I say, I forget the sunscreen. I live a little more freely.

PS: thank you so much for reading skin issues — this is a free issue, and it still takes me a lot of work to write, think and edit all of what you just wrote, so if you could spare a like, share or comment on this post, I would be super grateful.